The False Assumption

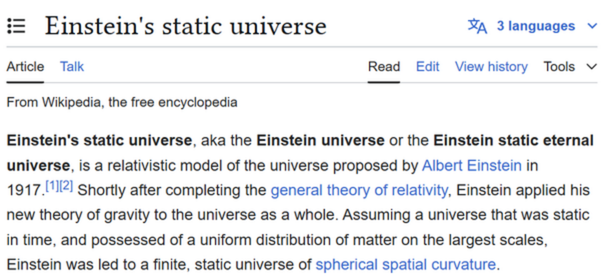

Picture the greatest minds in science, working with the best math of their age — and still getting something big wrong. For centuries, philosophers and scientists believed the cosmos was fixed: an eternal, unchanging stage where stars and planets moved but the stage itself did not. Even Albert Einstein, wrestling with his equations of gravity, couldn’t accept an expanding cosmos. He added a ‘fudge factor’ to force his model to be static. Why? Because an expanding universe felt impossible. That assumption has been respected, widely held and shaped modern thought right up until the 1920s.

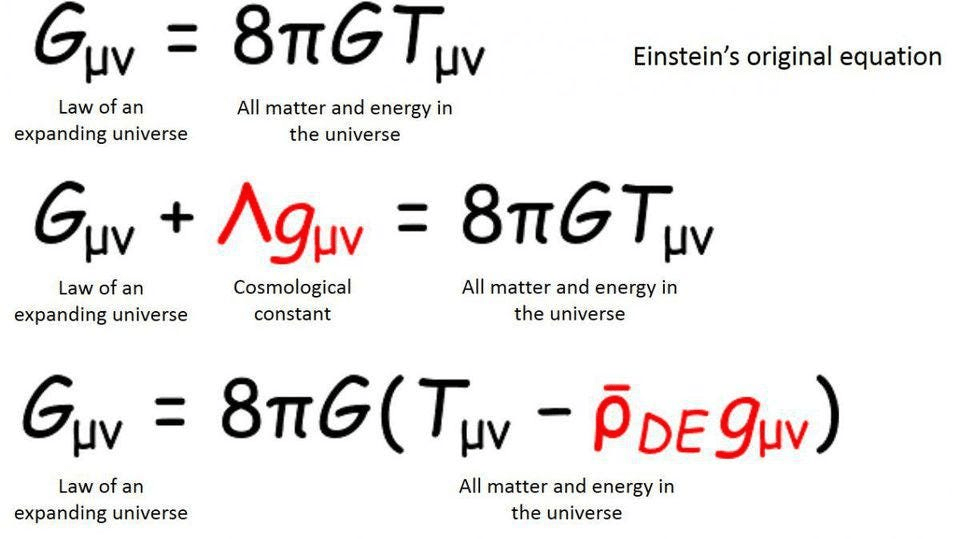

Einstein introduced the cosmological constant (Λ) to his equations to prevent expansion, literally to “keep” the universe steady. His initial equation of General Relativity actually projected that universe is expanding, contradict with the prevailing view at the time.

He literally forced his model to be static because an expanding universe felt impossible. Einstein’s belief that the universe was static did not come from a vacuum. It was the product of more than two thousand years of intellectual tradition, stretching back to ancient Greece. The idea began with Aristotle, who taught that the cosmos was eternal, perfect, and unchanging. To him, the heavens were made of an incorruptible substance that never aged or decayed. The stars, seemingly motionless and constant, reinforced his conclusion that the universe must have always existed in this flawless equilibrium.

When Isaac Newton revolutionized physics, he too assumed the universe was static. Though his law of gravity implied attraction between all masses, he reasoned that in an infinite, uniform universe, those forces might balance perfectly, preventing collapse. This idea fit comfortably within the Aristotelian heritage.

By the time Albert Einstein formulated his general theory of relativity in 1915, the static-universe assumption was still the default. His equations predicted either expansion or contraction is an unsettling result that challenged two millennia of philosophical certainty. Unwilling to abandon the age-old belief, Einstein added the cosmological constant (Λ) to his field equations, creating an artificial balance to hold the universe in place. Only after Edwin Hubble’s 1929 discovery that show galaxies moving apart, did Einstein reluctantly concede that the universe was expanding, calling his earlier adjustment his “biggest blunder.”

Einstein’s Move and the Scientific Pivot

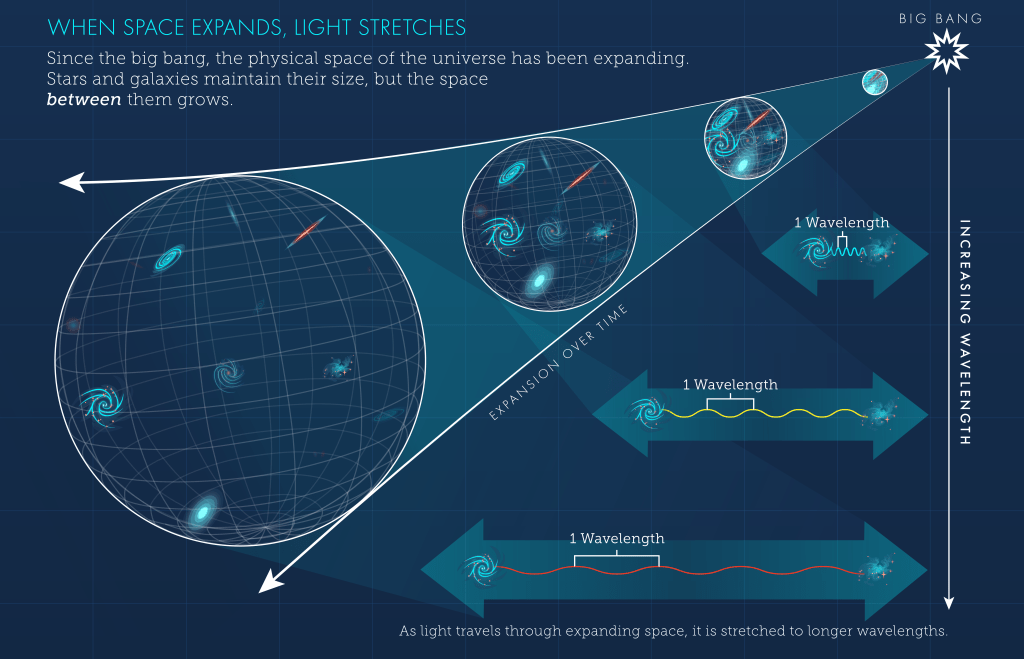

In 1929, Edwin Hubble made one of the most transformative discoveries in the history of science. By observing distant galaxies through the powerful Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, he noticed something extraordinary: nearly all galaxies were moving away from us, and the farther a galaxy was, the faster it receded. This observation became known as Hubble’s Law. The conclusion came from analyzing the light emitted by these galaxies. When Hubble examined their spectra, he found that the wavelengths were shifted toward the red end of the spectrum—a phenomenon called redshift.

According to the Doppler effect, this redshift occurs when an object moves away from the observer, indicating that space itself was stretching. From this, Hubble and later cosmologists realized that the universe was not static as once believed, but expanding continuously.

Revelation: The Divine Pivot of Human Understanding

Now pause. A short sentence was revealed in 7th-century Arabia that reads:

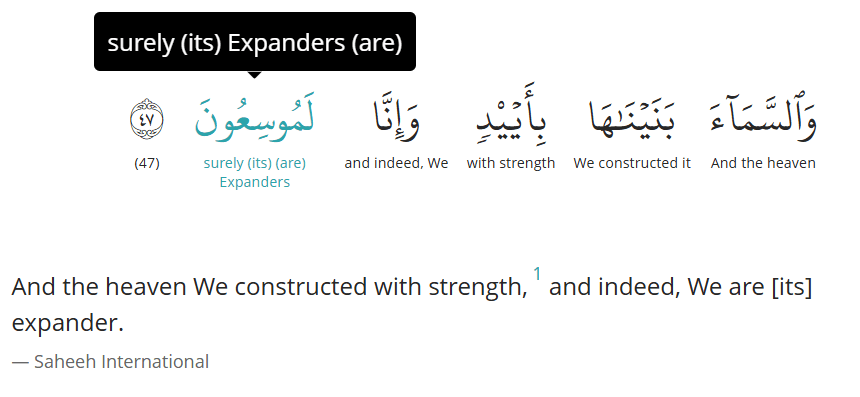

“And the heaven We constructed with strength, and indeed, We are [its] expander.”

– Surah Adh-Dhariyat (51:47)

Three details make this line extraordinary:

- Tense and verb choice. The Arabic lamūsiʿūn comes from a root meaning ‘to widen’ — and the grammar gives an ongoing sense: we are expanding, not we expanded once. That’s a statement of process.

- Concept match. Modern cosmology doesn’t just say galaxies move apart, it says space itself expands. The verse speaks of the heavens being made wide — unusually close to the concept that space is stretching.

- Timing. This was written more than a millennium before telescopes and Hubble’s observation. No known observational basis existed then to suggest the heavens were actively expanding.

Skeptics will say: you can read modern ideas into old poetry. That’s fair — but note the combination of precise tense, the idea of widening, and the historical impossibility of observing cosmic expansion back then. Combined, these make the match more than casual coincidence. It’s linguistically specific, scientifically resonant, and historically surprising.

If the universe is still being stretched, it suggests the cosmos is not a finished artwork but an unfolding act. That flips the script on the static universe idea — it implies a dynamic creation, one that continues to develop. For many, that’s not just scientific fact — it’s a theological and existential nudge: the Creator is not remote; creation is active.

So: a centuries-old sentence that reads like a line from modern cosmology. Coincidence? Deep metaphor? Or foreknowledge expressed in language that science only later clarified? Whatever you feel, the verse makes you stop and look up — and when you do, the sky seems wider than before.

Einstein and the world assumed the universe was static. He even added a term to his equations to make it so. Then Hubble showed space itself is stretching. Now read this 7th-century line: ‘We are its expander.’ Not ‘We expanded’ — we are expanding. A sentence written 1,300 years before Hubble. Goosebumps? Decide: coincidence or something more.

| Linguistics | Astronomy | Biology | Entomology | Genetics | Oceanography | Geology | Physics |