The Quran Claims the Earth And the Sky Were One Flat Piece

Critics claim that the Qur’an describes the earth and sky as a single flat piece that was later separated. They argue that this reflects an ancient myth rather than divine revelation. But such a claim falls apart the moment we engage with the Arabic text, its semantic structure, and the scientific phenomena it describes.

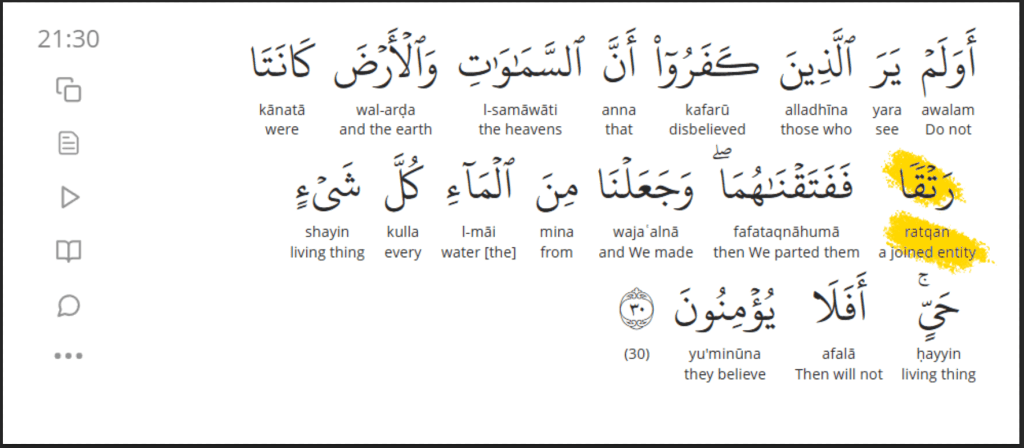

This allegation is referring to the Surah Al-Anbya:

The Verse and Its Precision

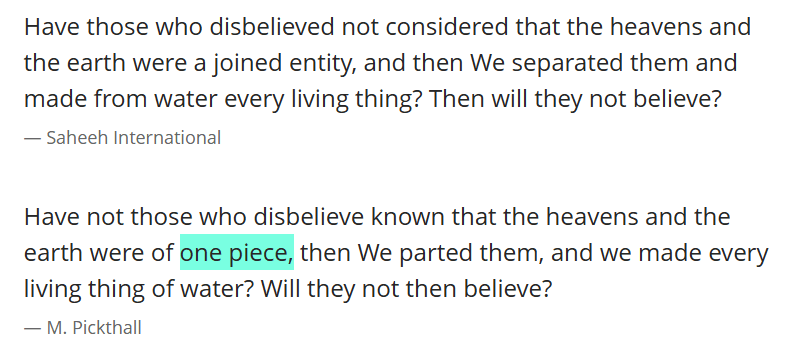

The variants of the translations indeed mentioned “one piece”. But it’s not explicitly flat. It just a translation anyway, what the reader understand.

At the heart of this verse is the Arabic term رَتْقًا (ratqan) — a word that has ignited centuries of commentary and remains one of the most fascinating intersections between revelation and cosmology.

The Arabic Root: Ratq (رتق) — Not Flatness, But Sewed Together

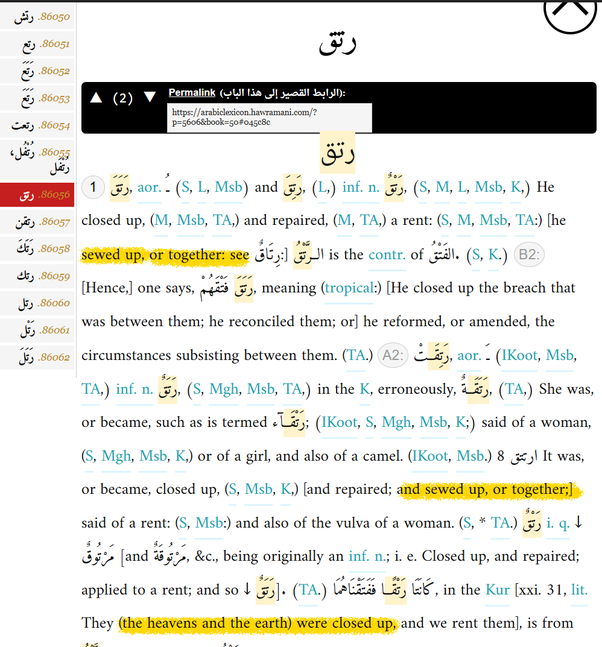

The claim that this verse implies a flat joined piece arises from a poor understanding of Arabic linguistics. According to classical lexicons such as Lane’s Lexicon, Lisan al-‘Arab, and Taj al-‘Arus, the root ratq (ر ت ق) means:

“To sew up, to close up, to repair, to make one continuous entity.”

Lane cites:

“He closed up, sewed together, or joined together that which was separated.”

“The heavens and the earth were closed up — ratqan — and We rent them asunder.”

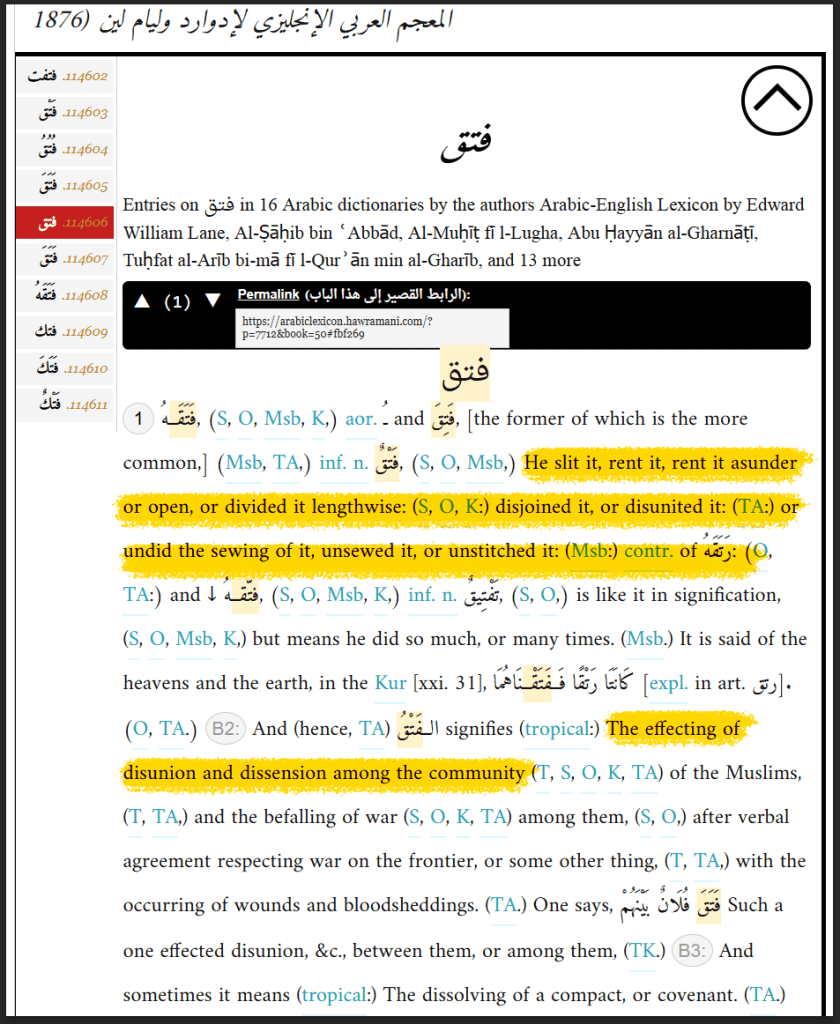

The opposite of ratq is fatqa (فتق), meaning “to split, to separate, to open.” The Qur’an says:

فَفَتَقْنَاهُمَا (fa-fataqnāhumā) — “We separated them.”

Now, what did this verse actually mean in its original context? That remains an open question and that’s exactly the point.

If we take the Qur’an’s wording carefully, the notion of the heavens and earth being joined together offers a compelling image. The universe, before differentiation, could have been in a state where matter and energy were undivided, forming a single continuum. It could indeed be a flat piece, a fusion, or something else entirely. What truly matters is the fact that it originated from a unified entity, a concept that is mind-blowing because it aligns perfectly with established scientific observations.

Thus, rather than picturing a “flat sky joined to the earth,” as literalists sometimes misinterpret, the verse could allude to a primordial unity. A single, undifferentiated existence that God then commanded to separate into what we now perceive as “heavens” (the cosmos, space, or unseen realms) and “earth” (the terrestrial or material domain).

It’s crucial to note though that this doesn’t require scientific confirmation. It isn’t meant as a physics lesson, but as a reflection on divine order and power. The Qur’an’s language operates at multiple levels; physical, symbolic, and spiritual and its brilliance lies in that layered depth.

Also, it is worth pointing out that revelation consistently spoke within the perspective and level of understanding of its initial audience. The world they knew was the world they lived in which is the earth beneath their feet and the sky above their heads. Therefore, it makes perfect sense that the Qur’an addressed cosmic realities in terms that were both familiar and comprehensible to them.

The Problem of Certainty

Yet some people, both believers and skeptics, attempt to “prove” or “disprove” this verse through scientific lenses. This approach often misses the essence. The Qur’an doesn’t ask us to become eyewitnesses to cosmic origins. It asks us to reflect on what we can observe, while recognizing what we cannot.

In Surah Al-Kahf (18:51), Allah directly addresses this boundary of knowledge:

“I did not make them witness the creation of the heavens and the earth, nor their own creation; and I was not one to take the misleaders as assistants.”

This verse strikes at the heart of epistemology: no human has seen the moment of creation. All claims whether religious speculation or scientific hypothesis are built on inference, not observation. We can model, imagine, and theorize, but not confirm.

Science itself, for instance, reconstructs the Big Bang through mathematics and background radiation, yet admits that the singularity itself; joined entity.

Similarly, theology offers revelation, but revelation is not empirically verifiable. It is known through faith, argumentation and reasoning, not through the senses.

A Verse That Withstands Time

The strength of the verse lies in its ambiguity — or rather, its transcendent elasticity. It neither locks itself into one cosmology nor contradicts evolving knowledge. Whether ancient Arabs understood it as a poetic expression of divine power or modern readers find it resonant with cosmology, the verse remains intact in meaning.

This durability contrasts sharply with the limitations of human theories. Science continually revises itself as new data emerges; paradigms shift. But the Qur’an presents its account in non-temporal, universal language. It speaks to all generations, not just one.

When it says, “the heavens and the earth were joined entity, then We separated them,” it captures an essential relationship: everything that exists came from a unified origin under divine will. Whether that unity was physical, metaphysical, or beyond our categories entirely, the message is the same — creation is deliberate, not random.

If we momentarily set aside the polemics and simply read the verse in light of what we now know, it’s difficult not to be struck by its precision. The idea that the “heavens and earth” — which in Qur’anic idiom mean the entire cosmos — were once a single entity that was later separated resonates powerfully with the Big Bang model.

The Qur’an’s description does not employ the technical jargon of 20th-century physics, nor does it need to. Its language is semantically open, capable of encompassing new meanings as human understanding evolves — which, in itself, is a sign of its timelessness. For a 7th-century text to describe cosmic origins as a process of fusion and subsequent separation is, at minimum, intellectually remarkable.

The Call to Reflection

The verse ends with a challenge: “Then will they not believe?” This is not an invitation to blind acceptance but to intellectual humility. It asks humanity to acknowledge the limits of their own knowledge and the grandeur of the unseen.

It’s as if God is saying: You look at the universe, the stars, the planets then do you not see how ordered and purposeful it all is? Do you not see that it once was nothing, and now it is everything?

By directing our attention to creation, the Qur’an reminds us of our position within it which is creatures who came after, who arrived long after the beginning. We can observe, analyze, and theorize, but we cannot witness what only the Creator has seen.

Conclusion

Surah Al-Anbiya (21:30) isn’t a flat-earth verse, nor is it merely a cosmological hint. It is a theological reflection expressed through imagery accessible to every generation. The heavens and the earth were once united, not necessarily in spatial form but ontologically, as part of a single divine act of creation. Yet what makes this verse even more mind blowing is that this very description, spoken in the 7th century, astonishingly aligns with the observable reality of our expanding universe. God’s act of separating them marks the beginning of structure, order, and diversity, the unfolding of a cosmos that emerged from unity. And still, the Qur’an reminds humanity of its limits:

“I did not make them witness the creation of the heavens and the earth…”

(Al-Kahf 18:51)

In other words, the details of creation are not for us to verify. What matters is the recognition, that everything around us originated from One Source, by One Will.

So the debate over whether “joined” means fused matter, a single realm, or an allegory for unity misses the heart of the verse. The point isn’t the mechanics of creation; it’s the truth that creation happened, deliberately and purposefully — and that none but God can claim firsthand knowledge of how.

| Linguistics | Astronomy | Biology | Entomology | Genetics | Oceanography | Geology | Physics |